Tags

bloodstock economics, modest proposal, opportunities in breeding thoroughbreds, sales and consignors

Over at Boojum’s Bonanza, that blog’s inquisitorial statistician has posted a story about 1969 Horse of the Year and Belmont Stakes winner Arts and Letters that was written by the legendary Daily Racing Form columnist Charlie Hatton. It’s an interesting piece and worth a look in itself.

In discussing the pedigree of Arts and Letters, which was quite good (1966 ch h by Ribot x All Beautiful, by Battlefield), Hatton also mentions that All Beautiful’s third dam, “Star Fairy, [was] one of two mares Will du Pont retained when producers were a drug on the market, and breeders would give you one and a halter in which to lead her off the place.”

That comment sounds shockingly familiar. Ah, yes, we’re back to the future!

As I advised an out-of-state visitor before the 2011 Keeneland January sale, “beware of people handing you a lead shank, they may walk off without telling you that you’ve just inherited the mare it’s attached to.”

The state of the breed and the economics of breeding are generally at that point right now. Despite the wealth of green grass and the bounty of improving weather, breeding racehorses is mostly red ink at present and has been for the greater part of the last three or four years.

And despite the great tail-wagging organizations with two-, three-, and four-letter labels, the only way out of this appears to be on our own.

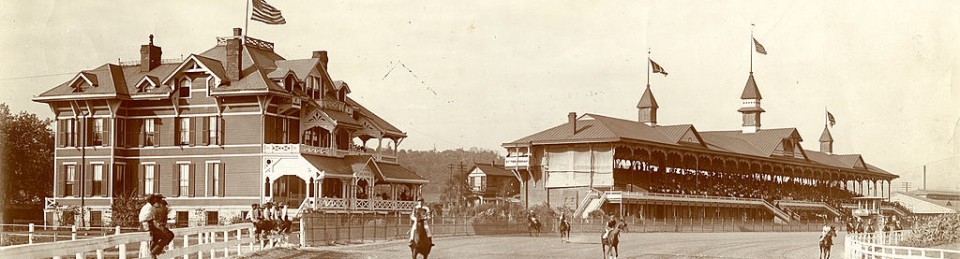

As I understand it, the Keeneland Association was originally started by the Breeders Sales, which was functionally a sales cooperative that gave breeders the opportunity to conduct their own sales, promote their own stock, and control the volume of production.

Yeah, that last bit is the key.

We are dying of oversupply right now, and it appears that is going to be the future trend for a couple of years, at least. Which means ….

So, instead of twisting in the wind, how about this? As a group, Kentucky breeders drop a third of their broodmare bands. We breed only to stallions with books limited to 80 mares. We form a very large breeder-owner cooperative to break, train, and develop the 30 percent to 50 percent of the yearling crop that really isn’t big enough, progressive enough, or finished enough to be a genuine commercial animal at 14 to 18 months.

That would make a difference for all of us.

We are not “dying of oversupply” of thoroughbred yearlings, we are dying of undersupply of owners who wish to buy and race them. The race card for May 11 at Delaware Park was cancelled because they only were able to fill five races. I believe the Jockey Club expects about 25,000 -28,000 mares to be bred this year, which will result in less than 22,000 registered foals. We need to find more end users and less pinhookers at the sales. I think it would be better to distribute purse money so there is more money for the non-stakes races…this would help keep more owners in the business. I also think we have to do something to reduce the vet bills….these can run $200 per race for supposedly healthy horses. In my opinion, we could do better with more owners and less veterinarians

Please expound upon “break, train, and develop the 30 percent to 50 percent of the yearling crop that really isn’t big enough, progressive enough, or finished enough to be a genuine commercial animal at 14 to 18 months.”

Somewhere between a third and a half of the annual yearling crop is average. They are nice enough horses, but they aren’t really big, thick, quick-maturing animals that racehorse owners or pinhookers want to buy.

As a result, these nice, average horses don’t even bring the cost of producing them. Look at Blind Luck as a prime example. There was never anything wrong with her, she was a nice filly, and she was not a profitable yearling or 2yo.

But when put into training, she came along nicely, won well in her debut, and then sold for a good profit. I believe if breeders band together, they can make the economics of breaking, training, and racing sufficiently equitable that these nice, average but non-profitable yearlings would be money makers as they become racing athletes.

fmitchell i think that is a great idea, you should hire me, i could make that work for you, 100,000.00 a year. plus 650.00 WEEK for riders, per 6 head plus 450.00 week for the grooms per 6 head , plus stall rent, plus workmans comp, plus hay, plus feed, access to artificial track, cant train here in ky on natural in winter. Plus a farm with a mess of paddocks to turnout. ROUND PENS WITH CHIPS AND SAND. GOT TO TURN EM OUT WHEN YOU BREAK EM. OH YEAH AND THHE DADGUM VETS, THEY GOT TO MAKE THEIR 500,000. A YEAR , PLUS BLACKSMITH. But most of all you got to know what your doing. Could it be done. Sure. Will it make your hair gray and fallout, oh yeah. What could be fun if you could pull it off, you and all your friends, keep the horses you think dont bring enough, break get them ready to breeze and have a undertack show there in lexington. I f any of em can run, folks will buy em. BITB SALES Hold it the day after derby.

I think the idea for breeders to drop a third of their broodmares is the wrong approach. First of all, KY breeders have already culled an enormous amount of mares in the past three years. I agree with Cynthia McGinnes that oversupply is no longer the real problem and what is really needed are more end users and fewer pinhookers buying our horses. We need to get back to our roots as a sport and not focus as much on the “industry.” Something is very wrong when it seems that the only way a breeder can get a horse sold is by allowing the many “middle men” along the way to reap most of the profits, despite the breeder spending the majority of the money and taking the lion’s share of the risk. The sport needs to reach out through better marketing efforts in order to bring in more end users. The market for luxury items is back on the rise as the wealthy begin to spend again. So why isn’t the market coming back for Thoroughbreds?

Secondly, if breeders drop a third of their broodmare band, invariably the majority of them will cull the less “commercial” ones. Which will exacerbate the problem of the breed being flooded with “market” horses. Culling even more of the less popular mares would most likely mean an even greater loss of diversity in our bloodlines, further polarizing our American Thoroughbred. Personally, I am trying to maintain a balanced broodmare band that includes more than a few mares considered by the market to be non-commercial, but that trace back to important two-turn bloodlines and have impeccable conformation. I think more breeders should do the same in the hopes that we improve our breed’s phenotype and soundness. This should eventually equate to more success on the racetrack and then in the sales ring. I believe the current commercial market is too focused on short-term success for quick monetary gain, encouraging breeding for mostly early-maturing sprinter-type dirt horses without regard for soundness or good conformation as those can be managed with veterinarian intervention. This is not helping our American Thoroughbred compete on or be marketable to the international stage and in America it is destroying a breed that was bred for centuries to run at classic distances. Breeding Thoroughbred racehorses is a long-term proposition and as stewards of the breed we are failing miserably due to market pressures.

Thirdly, what happens to all of those broodmares that are culled out of production? Do their breeders have a plan for them? Are they just retired for a few years and then brought back into production? If so, then most KY stallion stations won’t want to breed to them after a long lull in their produce record. Nor will the sales companies allow them through their rings if three or more years have lapsed. And if they are not ever bred again, then what becomes of those mares? Most that are culled are likely to be older and therefore less likely to be retrained as riding horses. Are we to just cast aside these broodmares who have served us as valiantly as the racehorses do on the tracks? Where are the rescue groups for broodmares? I know of only one that focuses exclusively on mares and they only have room for a few at a time. Unless there is a quality support network for retired broodmares in place, I believe it would be irresponsible for KY breeders to just dump even more mares.

I do like your suggestion of putting together a breeders’ cooperative to get the horses that don’t sell to the racetrack. This is an idea that should be embraced by KY breeders and would enable more breeders to breed their horses for the right reasons rather than just for short-term financial gain. Where can I sign up?